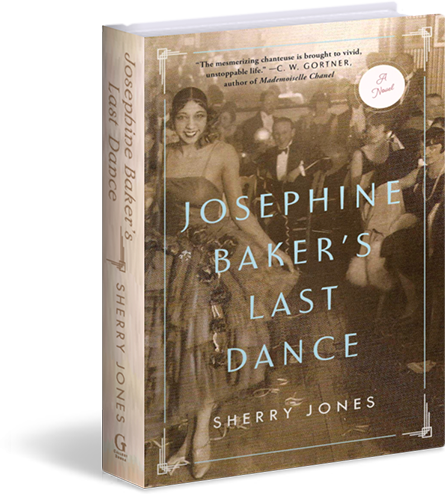

A Brand New Novel

Josephine Baker, the early-20th-century African-American dancer, comic, and singer–hugely famous in Paris. Did you know that she was also a spy for the French Resistance during WWII?

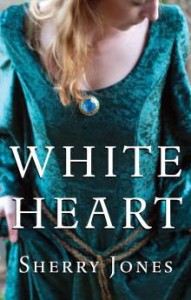

She sweeps into the hall clad in spotless white, the color of angels and mourning queens. Pierre Mauclerc’s eyes gleam at her, lurid with imagined sin, but he has seen nothing as yet. He sits on his bench with his lips to the ear of Hugh de Lusignan, whispering lies while forty other barons of the realm mill and chatter, their exclamations and barks of laughter bouncing about the stone walls as Blanche begins to remove her clothes.

She stands in their midst, her head high, her white-gloved hand lifted to the white cord tying her ermine-lined mantle across her chest. Down it falls into the waiting hand of Mincia, her maid. Pierre’s mouth ceases to move. Heads turn her way; eyes pop at the sight of her face, made up in the shape of a startling and, she hopes, poignant, heart. Her lips are white, her eyebrows. They used to call her “white in heart” and they will again, by God.

She slides her white velvet surcoat over her arms and drops it into Mincia’s care. The hall falls hush as if words were birds settling in the rafters, rustling their wings. Mincia draws a knife from the sheath on her hip and, with a flash of the blade, cuts the threads tying the sleeves of Blanche’s gown to her outstretched arms. For this occasion she has donned her tunic of white silk embroidered with white fleurde-lis, the emblem of France. Five pearl necklaces drape across her chest, hiding her flush but not her breasts, which must be fully revealed.

Mincia dips to the floor to grasp the hem of her dress. Slowly she lifts it as the barons watch, jaws dropping (a frisson of pleasure runs through Blanche’s veins. Let them gossip about her now!), revealing her white calfskin boots and white silk leggings—a queen must not cry, blow her nose, or bare her feet and legs in public.

“My lady!” Robert de Gâteblé, Pierre’s elder brother, leaps to his feet. “Please stop.” He looks as if he might weep, the poor man. He fears she might debase herself—but it is too late for that. Her enemies have already degraded her, and gleefully so. To what lengths will they go to wrest the Crown of France from her? No matter: To keep it, she will always go further.

A woman’s power lies in her beauty. So said her grandmother, Eléonore d’Aquitaine, who ought to know. Today, beauty feels more like her undoing. But no. Were she as ugly as Medusa, these men would murmur against her, for she possesses what they most desire: power.

Continue, she whispers to Mincia, who has halted with Blanche’s gown in her hands, waiting to see if she will change her mind. Hoping. Do not give them the satisfaction, my lady, she begged just moments ago as Blanche looked down over the hall, waiting for the room to fill. She is doing the opposite, can’t Mincia see that? They will not be satisfied until she is ruined—which will be very soon, unless she puts an end to these lies.

Mincia lifts the heavy garment up, up, blocking Blanche’s white-hearted face from view, exposing the rest of her. Someone sucks in his breath. She hears a curse. Good! The room’s chill air grips her torso with icy hands. Gooseflesh ripples her skin. She bends her knees; Mincia pulls the tunic over her head without even knocking her crown askew. Exclamations fill the hall.

Blanche never drops her glance. She knows how she appears, her nipples pushing darkly against the thin chemise of fine white linen, her belly not only flat but concave, her hipbones jutting, the sheer fabric clinging to the hair between her legs.

“Monsieurs, we have heard rumors,” she says. Her voice does not quaver, although her bare arms shiver. The barons’ eyes slide down her body; jerk back up to her face, their cheeks reddening; then slide downward again. She might as well be naked before them, which is her intention. Isn’t this how they have imagined her?

“Look upon us, yes! Fill your eyes.” Pierre Mauclerc—“Bad Clerk,” his name means, and although no one knows how he acquired it, Blanche can easily guess—glares at her. He has lost this game, and he knows it. But did he really expect to triumph over Blanche de Castille?

“White in heart as in head,” people used to say of her twenty-seven years ago, when she arrived in France to marry the prince Louis. Perhaps her grandmère had this sentiment in mind when she chose Blanche over her older sister to become France’s next queen. “Blanche will be an easier name for the French to pronounce” was her excuse. Its connotation of whiteness may help her now, please God.

“We have heard it said that we are with child.” She turns her body this way and that, giving all the room a full view of her stomach sunken, like the rest of her, by grief; her smallish, unswollen breasts. “Is this the body of a pregnant woman?”

Thibaut is licking his lips, damn him to hell. Were it not for him, she would not be in this predicament.

“Have you seen enough?” She lowers her gaze to them, meets Pierre’s whip-like glare, the as-yetbeseeching eyes of Robert de Gâteblé. One by one they look away like bashful children caught in some wicked deed. “Does anyone still believe we’re carrying the child of Romano, the cardinal of Sant’Angelo?”

Her voice snags on his name. She looks down her nose at them, daring them to notice. Romano. Gone this morning with a final kiss, his fringe of hair curling darkly over his soft Italian eyes, his soft hands like warm milk on her skin. The taste of him lingers on her tongue.

Thibaut stands. “We have seen all we need to see.” He rushes over to her, his chins jiggling. His breath comes in labored pants. He snatches the gown from Mincia’s hands and holds it high over Blanche’s head. “May I?”

She lifts her arms. He slips the gown gently over her head, then over her shivering body.

“It is evident to me, monsieurs, and it should be to you, as well, that our queen is innocent,” he says as Mincia and Eudeline finish dressing her.

“Perhaps now,” Robert says, “these terrible rumors will cease.”

“Cease they must, monsieurs, for I have now proved them to be lies.” She gives Pierre a pointed look. She imagines him swinging from a noose, and a smile tugs at her lips. His face turns as pale as her own. “You all know the penalty for treason,” she says and sweeps around to ascend the stairs, the taps of her booted feet on the stone the only sound audible in the great, stunned hall.