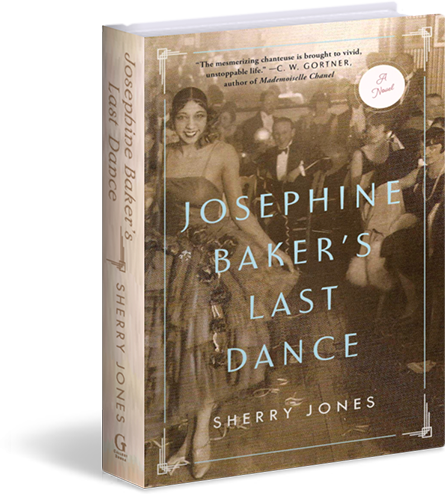

A Brand New Novel

Josephine Baker, the early-20th-century African-American dancer, comic, and singer–hugely famous in Paris. Did you know that she was also a spy for the French Resistance during WWII?

Hardcover: 432 pages

Publisher: Beaufort Books, Inc.; 1 edition (October 2008)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0825305187

ISBN-13: 978-0825305184

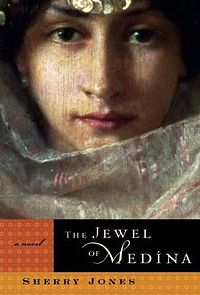

Born Aisha bint Abi Bakr in seventh century Arabia, she would become the favorite wife of the Prophet Muhammad, and one of the most revered women in the Muslim faith. Married at the age of nine, The Jewel of Medina illuminates the difficult path Aisha confronted, from her youthful dreams of becoming a Bedouin warrior, to her life as the beloved wife and confident of the founder of Islam.

Extensively researched and elegantly crafted, The Jewel of Medina presents the beauty and harsh realities of life in an age long past, during a time of war, enlightenment, and upheaval. At once a love story, a history lesson, and a coming-of-age tale, The Jewel of Medina provides humanizing glimpses into the origins of the Islamic faith, and the nature of love, through the eyes of a truly unforgettable heroine.

“The Jewel of Medina” is an international best-seller, with translation rights sold in 20 languages.Check out some of the foreign editions here.

“The Jewel of Medina” book trailer:

Read the Wall Street Journal editorial, “You Still Can’t Write About Muhammad,” that started the world-wide controversy over “The Jewel of Medina”: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121797979078815073.html

An Author’s Response to a Previous Review from Raging Bibliomania:

Last month I reviewed The Jewel of Medina, a historical fiction novel that dealt with the Prophet Muhammad and his child bride Aisha. Although I found the book interesting and timely, I had some quibbles with the plot and characterizations. Mostly I was concerned with the portrayal of Muhammad, which I felt was somewhat dubious. After posting the review, the books author, Sherry Jones, was kind enough to send me an e-mail which answered many puzzling questions I had regarding the book. I thought I would share this e-mail, as I found it both enlightening and edifying.

Dear Zibilee,

Thank you for reviewing “The Jewel of Medina.” I’m glad you enjoyed it for what it is: An enlightening tale of the origins of Islam, and a story about the difficulties of harem life.

Zibilee, my portrayal of Muhammad as a sexual man is accurate according to the Islamic traditions. One tradition tells how Muhammad had intercourse with all his wives every night, and ends, “Allah gave him the strength of twenty men.” Some traditions say he had as many as 20 wives at one time, although I could only verify a total of 12 in his harem. Those of us who grew up with Christianity are so used to separating spirituality from sexuality that we have a hard time holding both in the same container. But, as the Tantric tradition demonstrates, the two can — and, perhaps, should — be intertwined.

Many books have been written about Muhammad the military strategist, etc. My goal was to tell about the women behind the man — his domestic life — and to portray the difficulties of life in the harem. It seems that you picked up on these difficulties. My information came from the Islamic traditions as well as many books about Muhammad and his wives.

And yes, the hype surrounding “The Jewel of Medina” has set readers up for disappointment. Things weren’t supposed to be like this, but I can’t do anything about it. I can only hope that, in time, the controversy will fade and people can approach the book for what it’s intended to be: A love story, a book about women’s obstacles and women’s empowerment, a look at the origins of Islam through the eyes of one woman, and a bridge-builder, showing us in this culture that Muslims are people, too, and that its leader was a man of compassion and gentleness.

I love to see my book discussed for its contents and not for the controversy. As a noted Italian literary critic said to me, “The scandal is nothing. The book is everything!”

All best,

Sherry Jones

Author/Journalist

http://www.authorsherryjones.com

The Jewel of Medina

From Siempre Leyendo

Synopsis: Aisha, favourite wife of the Prophet Muhammad, isn’t made for a life of imprisonment and submission to men. She has a head of her own and longs for a life of freedom and equality. This brings her into trouble numerous times during her life from age 6 on, when she is promised to Muhammad, until 19, when her beloved husband dies. Nevertheless, Aisha learns to control her emotions and use her wits to convince Muhammad and the people around her of the value of listening to women.

I was quite skeptical about this book at first. Sherry Jones isn’t a Muslim; she has never lived in the Arabic world. Furthermore someone said to me she feared it must be horrible kitsch. However, I was positively surprised. Jones writes in the appendix what she has made up and what is historically proven. She explains her intentions and goals and writes about the difficulties of getting her book published, how Bllantines, a group of Random House, refused to do so out of fear of terrorist attacks (without having received any threats, that is). But also how she received support form moderate Muslims who thought it important to publish fiction about Muhammad and Islam. I’m very curious about the sequel which is supposed to cover the first Islamic war told form the view of Ali (a figure revered by the Shiites) and Aisha. I think Jones is doing a very important thing here, bringing Islam into mainstream culture, far from terrorism and war.

Here’s a review of my Dec. 4 lecture at Carroll College in Helena, Mont., by a reporter for the Carroll Prospector:

Controversial author speaks: Jewel of Medina: Too hot for Carroll

By Samatha Tappe, Lead Writer

Riding on the back of Carroll’s newly adopted “Speaker’s Policy,” Sherry Jones pranced onto campus without har-ness. Author of the controversial new book, Jewel of Medina, Jones came to discuss self-censorship in a presentation entitled “To Hot for Random House: The Jewel of Medina.”

Refreshingly approachable, wearing a completely out of place black cocktail dress, and consistently over-acting her pre-typed speech, Jones was the most inspiring thing to come to Carroll in some time.

“My name is Sherry Jones,” she began, “but I’ve been called a lot of other things these past few months.”

Not the least of which are “Islamopanderer,” “sugar-coater of pedophilia” “dirty sex worker” and “world’s most dangerous author.”

Jones’ impressive repertoire of inflated nicknames was collected scandalously close to the book’s release, leading Jones to believe that most of her insult-hurling critics didn’t even read it. While she admittedly enjoys “pushing the envelope,” she genuinely seems to be confused about the hubbub.

The book intends to personify the youngest wife of the Prophet Mohammad, 6-year-old A’isha. To properly introduce the world to A’isha, Jones fictionalized parts of the story in order to bring her to life. That, along with purported soft-core pornographic content, seemed to be the base of said hubbub.

In all fairness, Jones is upfront about the parts she fictionalized, and calls the book historical fiction. And the “soft-core pornography” is A’isha’s account of witnessing some neighbors having sex. Blunted by the innocence of a six-year-old’s description, the scene is more comical than scandalous.

More than once during the hour, however, it seemed the title of the presentation could be changed to “Sherry Jones: Too Hot for Carroll College.”

She told a red-faced crowd of college boys and elderly ladies alike, “There are no sex scenes in my book, unless you count A’isha glimpsing a couple in the copulatory act, which to her six-year-old’s eyes resembles a hairy goat’s bladder ball slamming into a flailing squashed beetle.”

Insert deafening silence, then hysterics; the mark of a truly shocked crowd. The laughter was indiscriminate of age, gender or religion. Only Jones could manage to make a crowd love being that uncomfortable.

Jones’ unabashed lack of inhibition is not practiced, and she obviously lost her compass in trying to navigate the delicacy of being in the public eye – all to the most wonderfully awkward and touching effect.

The Jewel of Medina gave Jones something to stand up and talk about. The book should surely be appreciated, but Jones is the real story. A woman who lives her values in a truly compulsory way, Jones will remember your name, respond to your emails, and never forget the time she spent at small newspapers.

The Books I Done Read, Seven Caterpillar Review

Sometimes I’ll throw books onto my library request queue (all of which I had to cancel today, since we’re moving in a week and I already have some 8 books out, and I was 3rd on the list for The Virgin’s Lover!!!) and then when it comes in months later, be all Why did I request that? I only get X number of free requests per year (ok, 50, which is loads, but I’m a total hoarder) so I only save them for books I’m dying to read, or for books that aren’t going to be checked in again until 2090, at which point I’ll be dead/raving/able to read by telekenesis.

All that to say that when I went to pick up The Jewel of Medina, I was all, Ok self-of-two-months-ago, you know best. And it wasn’t azmazing. I mean, historical fiction is totally my shit, and foreign-fiction (i.e. bathrobe-travelling) is also up my alley, so a book set in Mecca (and then Medina, and then the desert for a bit, and then Mecca again) circa 627 CE, is defs my cup of tea. Especially when that book involves a man with TEN WIVES! Just think of the drama that ensues when your harem is ten large.

It also wasn’t total garbage. The language is a bit ‘scandal blew on the errant wind’ for me, but the story is engaging enough that all the adjectives sort of fade into the background after a while. The child-bride protagonist, A’isha, keeps trying to win her husband’s love with jealous fits, but the girl is something like nine when they get married, and nine-year-olds are idiots. Only sometimes does she get all, I learned a powerful lesson that day, that love is not only a feeling but also something that you do, etc etc etc for a paragraph or so, and then falls right back in to bitching about her co-wives and their voluptuous bosoms.

It took me about half the book to realize why I’d snagged it. THE CONTROVERSY, y’all! The ten wives are the wives of the Prophet Muhammed!! And some of them are painted a bit trashy, and Muhammed doesn’t always come out looking awesome, and anytime you make historical (holy) figures into real people with beards and lusty eyes who collect wives like monogrammed spoons, you’re going to run into some hate-mongering. Which Jones did, a leetle bit before Random House decided not to run her book, and muchasness after she finally got it published. I mean, freakin’ Muhammed, people!

I thought the book was fair. I mean, Muhammed was a man, right? I don’t think he ever claimed to be more than a man, with human failings, who just happened to receive the word of Allah. I don’t know, I’m not Muslim (neither is Jones, btw. She just wants to promote greater understanding and junk, and I am FOR it!), and that might be why I didn’t get my knickers in a knot. I mean, probs if the leading man was Hey-zoos, I’d be feeling a bit touchy. But it wasn’t, and I didn’t!

So hows about you? Have you read this? Are you Muslim? Have you ever read a book where someone who (in your opinion) sheds holy-water-tears was treated as flesh-people? What did you think?

Spill beans, folks.

Also, seven caterpillars.

The Literate Housewife Review

A’isha is a 6 year old girl who, after her parents betrothed her to Muhammad, the Prophet of Islam, was required to remain in her family home until she had her first menstrual period. For an adventurous girl such as herself, she is tortured by the limitations placed on her simply because she was betrothed. She dreamed of escaping to freedom with the Bedouins with Safwan, her childhood friend during the entire length of her purdah. When she witnesses a woman from her clan dragged away by a man who would disgrace her as well, A’isha can barely contain herself from taking up a sword and defending her neighbor herself. She may have been young and she may have been a girl, but she had the heart of a warrior. It was this spirit which caught the eye of Muhammad and changed her destiny.

I first heard about this novel in August when it was reported that Random House was pulling its publication for fear of angering Muslims and perhaps inciting violence. This reminded me of the events surrounding Salmon Rushdie and The Satanic Verses. I found the decision disappointing. Self-censorship out of fear of what might happen is in some ways worse than forcible censorship because it isn’t always as visible. How many other books have never been published out of fear? Thankfully, it was finally published by Beaufort Books in the United States. When I snagged a copy of this book through LibraryThing’s Early Reviewers program, I was very curious to see just what it was that caused such a large publisher to back down. This is a novelization of a portion of Muhammad’s life through the eyes of his most notorious wife. Still, he was portrayed with warmth and empathy. His charisma and love of Allah are obvious, but so is his humanity. While I suppose any fictionalization of Muhammad may anger some Muslims, no offense was intended. Canceling this publication was much ado about nothing.

As most established religions have struggled against the treatment of women and their roles in society, A’isha’s character is especially interesting as (to Western eyes) Muslim women seemed to be the most imprisoned by their faith, family, and spouse. The only issue I had with this novel was the story line surrounding the way in which the rules surrounding facial covering became part of Muslim life. Making a vision seem convenient to Muhammad felt like an “easy out” that was not at all in line with his character. I do not know exactly how this came to be part of the Islam faith, but it seems to have sprang more from the existing culture than from Allah.

The Jewel of Medina is a fast paced and engrossing look at the beginnings of Islam through the eyes of a young girl who eventually becomes the third wife of the Prophet Muhammad. At the beginning I was reminded of The 19th Wife because of the common themes of plural marriage and being married to a prophet. The 19th Wife and The Jewel of Medina are both ambitious novels attempting to provide insight on the origins of world religions through the stories of the women involved. Interesting that both novels would be published this year. For me, Jones’ novel worked where Ebershoff’s did not. From the moment that A’isha is married to the much older Muhammad, I could not put the book down. This novel’s insights into living among sister-wives were more compelling and, as there is only one voice telling the story, the reader is always fully aware of the opinions coloring the story. While we can’t truly understand today without knowledge of the past, by leaving the modern out of The Jewel of Medina Sherry Jones brought early Arabic culture and the roots of Islam to life without much of the cynicism of today.

I cannot recommend this novel enough. It is a wonderful way to learn about the origins of Islam through the eyes of a complex and strong young girl and then woman. A’isha does not conform to my ideas of a typical Muslim woman anymore than she did during her day and age. She had to fight for her place in Muhammad’s harim and for the place of women in her society. Being so much younger than her husband, A’isha’s story does not end upon Muhammad’s death and I am eagerly waiting for the sequel. The Jewel of Medina, like all of the historical fiction I’ve enjoyed, has peaked my interest in Islam, Muhammad and his wives. I absolutely enjoyed the adventure and I’m sure you will, too.

Asma, writing on the GoodReads website, gives “The Jewel of Medina” four stars:

I finally finished a book! Yippee! So, yes, as Muslims have criticized, this book depicts the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). BUT, the author isn’t Muslim so she isn’t restricted by this guideline. While some aspects are weak and would give much fodder to Muslims to be offended over, OVERALL, the book is a work of a fiction, so we shouldn’t let these details get to us. Of course, Ms. Jones had to “imagine” a lot of details that were not ever recorded (especially about the Prophet’s wives’ inner sanctum), and she did have to add some lush, fictional, non-historically based flourishes. But, come on, is this really that big a deal? The author acknowledges in a closing note that she did fictionalize and use literary devices.

Beyond that, there are several good aspects to this book. It vividly illustrates the savagery of the Quraysh, the Meccan tribe that constantly tried to kill Muhammad. It will help you to understand why Muhammad was a warrior and had to fight.

I think she also portrays the Prophet’s generosity to his wives, his progressiveness on women, fairly well. Are there things in there that might offend a Muslim? Sure! Do they take away from the positive image one gains of Islam from the book? Not at all!

Considering the truly offensive stuff out there on Muslims and Muhammad, this novel is not a big deal and is actually pretty useful in these times of general ignorance about Islam.

Especially recommended to fans of alternate histories like “Wicked” and “The Mists of Avalon.”

A’isha in a New Light

By Sangeeta Mehta

Updated December 2008

As the newspaper articles and blogs explain, it was Islamic studies professor Denise Spellberg’s comments about Sherry Jones’ novel The Jewel of Medina that led to a decision by Random House to abruptly cancel the project. Among other comments, Spellberg characterized the book as “soft core pornography.” Two questions come to mind: one, is this claim valid, and two, does it matter?

The Jewel of Medina opens with the word “scandal.” The protagonist, A’isha, is fourteen and describes what the crowd sees upon her return to Medina: “my wrapper fallen to my shoulders, unheeded. Loose hair lashing my face. The wife of God’s Prophet entwined around another man.” This man is Safwan, whom A’isha has wanted to marry since childhood. As she approaches home, someone cries out, “Al-zaniya” (“adulteress”); others chant “A’isha – fahisha!” (“fahisha” meaning whore).

The novel then goes back in time, beginning with A’isha’s story from the time she is six and talk of her future husband begins, and ending with the death of her husband Muhammed when she is nineteen and he is in his sixties. A curious and precocious six-year-old, A’isha, along with Safwan and another friend, decide one day to spy on a bridegroom having sex; they notice his “broad, naked back as he lifted his body off the bed then slammed it down again and again.” They stare “at his behind, as big as my goat’s-bladder ball and covered with hair, as it clenched and relaxed with each thrust.” A’isha inadvertently admits her wrongdoing and is punished: she is placed in purdah, unable to step outside her parents’ home until her wedding day.

Three years later, when the Great Day arrives and A’isha tries to cover her “budding breasts,” her (half-) sister Asma tells her she can no longer hide them. “‘Starting tonight, you’ll have to share them with your husband.’ She winked at me. ‘Just hope he doesn’t nibble too hard.'” Since A’isha has not yet begun menstruating, the marriage is not consummated immediately and A’isha continues to live at her parents’ home where Muhammed visits her, affectionately calling her “Little Red.”

Nor is the marriage consummated even after A’isha goes to live with Muhammed and his wife Sawdah. For years to follow, the consummation, which Asma describes as “hands like scorpions scuttling across your skin… and then—the sting of his tail between your legs!” is the primary goal that consumes A’isha’s mind. She adorns her hands with henna; she tries an aphrodisiac; she learns “a dance to make a man wild.” When she is chosen to accompany Muhammed on an expedition, she attempts to seduce him once again: “I pressed my body against my husband’s… I opened my mouth to invite his tongue to dance with mine.” She tells him, “After your victory, I’ll show you more.”

But Muhammed continues to see her as a child. A’isha’s resentment of her sister-wives grows, keenly aware of the beauty and power of each new wife Muhammed brings home. For instance, Umm Habiba, whom Muhammed considers marrying until, as A’isha discovers, she turns out to be a spy, is described as having “high cheeks like figs, eyelashes as long as a lover’s kiss, lips as full and dark as forbidden wine, skin like coffee, and a bosom like the twin hills of Mecca.” It is only after A’isha is deemed innocent for having been caught with Safwan, fives years into her marriage, that “desire burned like a fire in Muhammed’s loins” for A’isha. She eventually gets pregnant but suffers a miscarriage.

A’isha’s focus on consummating her marriage is not the only topic covered by The Jewel of Medina. The novel also includes scenes in which men gaze at or attempt to touch women, telling them they’d “pay in gold for a feel of those glorious breasts.” It describes “the mood in al’Lah’s holy mosque” upon the arrival of Muhammed’s wife Zaynab as “lewd and leering, filled with bawdy jokes and winking speculations. See how the Prophet lusts for his bride.” The novel is also replete with platitudes about the meaning of love. When A’isha doesn’t understand Zaynab’s need to make Muhammed happy, Zaynab tells her, “It’s called love, A’isha. Perhaps someday you’ll try it.” A’isha eventually realizes that “love was more than a feeling. Love was something you did for another person.” Earlier in the novel, A’isha seems to show another sign of maturity when she helps Umm al-Masakin with her daily work of helping to feed and care for the poor; A’isha finds “an inner peace I never thought possible” and later comforts Mother of the Poor on her deathbed.

Yet soon after her grief subsides, A’isha continues to speak her mind and compete with her sister-wives. Later in the novel, A’isha is triumphant in that she achieves her lifelong goal of becoming a warrior; she even encourages other woman to learn to protect themselves and their children with their swords—except that, as Jones admits in the author question and answer section of the novel, she has never read anything about the real A’isha wielding a sword. A’isha also achieves her objective of becoming the hatun, first wife of the harim—but this, too, as Jones admits, is a fabrication of historical events, an idea “which I picked up from reading about Turkish harems of later times.” The idea of purdah is also not consistent with Islamic teachings.

If The Jewel of Medina is “extensively researched” as the jacket flap claims, this research does not appear to be widely incorporated into the story. A’isha’s character is shown to possess some intriguing qualities: the ability to help Muhammed strategize in war, entrepreneurial pluck. But given the intense focus on her desires and that of others, she hardly comes across as admirable. According to the dominant Islamic scholarship, A’isha is best known for being Muhammed’s favorite wife, in whose company he received the most revelations; and while the novel ultimately depicts her as such, A’isha’s historically revered charachteristics are not salient. On the other hand, Muhammed’s character is portrayed as being positive: he is shown to choose his wives for protection against enemies rather than for his own needs; he is also described as gentle and compassionate, particularly toward A’isha. But no other character, except perhaps Mother of the Poor, comes across as sympathetic or layered. The greater themes in the novel—sex, jealousy, destiny—are the stuff of romance novels. Do these themes, coupled with chapter titles like “Troublemaker,” “Ridiculous Rumors,” and “Come Away with Me,” make The Jewel of Medina “soft porn”? Hardly. But they do remind the reader that this novel is just that, a fictional account.

In her author note, Jones asks her readers to join her on a journey to “another time and place, to a harsh, exotic world of saffron and sword fights…” She does just this, but her portrayals of the most esteemed figures of Islam are more exotic than nuanced, more entertaining than informative, more trite than thought-provoking, less historical and more fictional than readers would—or should—expect. Was Jones’s motivation to write this novel to “honor” A’isha and other women, given that her descriptions of them are more sexualized than anything else? Does she “have huge respect and regard for the Muslim faith,” considering that her presentation of this faith is so narrow in scope? Did she fictionalize a sacred history to help bring it renewed attention, or was this mission superseded by the aim of writing a novel, no matter the subject?

Jones certainly has every right to defend her intentions; and she has the right, as anyone does, to enjoy her freedom of speech: to interpret historical or any figures—regardless of religion—in any manner she chooses. And she cannot be faulted for claiming that her original publisher’s decision to pull her book—especially so far into the production process—was an act of cowardice. She is justified in praising Beaufort Books’ decision to undertake the publication of this work, especially in the light of such daunting circumstances as protests and a firebombing at the office of Gibson Square, the book’s UK publisher.

The bigger issue to consider is how the novel has been pitched and perceived by publishers, readers and critics alike. To view The Jewel of Medina as anything other than a romantic fiction based loosely on the life of A’isha, wife of Prophet Muhammed, is to completely undermine the humanistic significance of the novel’s revered figures.

Sangeeta Mehta has worked as a book editor at Simon & Schuster and Little, Brown. She is currently a freelance editor living in New York City.

Controversial The Jewel of Medina: Jones should be thanked, not reviled

(Reprinted with the author’s permission, this review appeared Oct. 27, 2008 in Frankfurt Allegemaine Zeitung, Germany’s most literary newspaper. The Jewel of Medina was published Nov. 3 in Germany by Pendo Verlag.)

By Stefan Weidner

When Sherry Jones’ controversial novel about Aisha, the prophet Mohammeds’ most well-known wife, hits German bookstores courtesy of Pendo on Monday, there is some curiosity as to the reactions. Will there be threats by radical Muslims like in the UK, where there was a firebomb attack on the house of the British publisher? In the US, Random House-division Ballantine had cancelled the contract with the author out of fear for the reaction of radical Muslims, purportedly after consulting with experts. This brought on a heated controversy, and understandably so: Did Random House turn itself into a trustee for the censorship desires of fanatical Islamists?

Once you read the book, and if you know the sources Sherry Jones references, the case seems completely bizarre. They are the standard works on the prophet’s life, written by Orientalists and Muslims, and among them is the voluminous compilation of Ibn Kathir (died 1373), one of the classical medieval sources on the legends of Aisha, which have partly been translated into English. The novel The Jewel of Medina begins with the most prominent of these legends, the so-called necklace affair, in which Aisha was accused of adultery after having left the caravan on a campaign and being returned only on the following day by a man from the rear guard. The episode seems to have stirred up so much excitement that according to tradition Allah sent down Quran verses 11 to 26 from the sura “The Light”, in which slanderers of respectable women are reprimanded. Sherry Jones reimagines the episode about the savior as a reunion with a childhood friend, but she too, lets Aisha emerge from it untouched. To speak of “softcore pornography”, as some sensationalist reports on the book have, is wildly inaccurate, the more so as the other chapters deal mostly with the jealousy and power struggles among Mohammed’s wives.

If there is a reproach to be made to the author, it would be that the book leans all too closely, in the dialogue sometimes even verbatim, on the historic Islamic sources. Were these any more well known in the West, accusations of plagiarism might have ensued. The complete plot, the dramatic climax, even the narrative perspective are provided in the Islamic Tradition – there too, it is Aisha who tells her story. This increasingly turns into a literary problem for the book. The characters attain no independent existence apart from that which is found in the sources. This cannot meet the expectations we have developed for a modern work of literature.

The close dependence on the sources produces a strange effect, which in turn makes the excitement about the book seem even more curious. The author treads so lightly in her treatment of Mohammed that you ask yourself now and again whether she might be a Muslima. For this is what a novel by one of the Islamic feminists who by donning the veil and invoking strong women like Aisha to claim their warranted Islamic rights with renewed vehemency, might look like in the near future. This notwithstanding the fact that the fifty-year-old Prophet’s marriage to the seven-year-old daughter of one of his closest companions became a focal point of anti-islamic propaganda – with Ayaan Hirsi Ali calling Mohammed “a perverse man” and the right-wing Austrian politician Susanne Winter dubbing him a “child molester”.

However, the book delivers no material for possible anti-islamic effects. Mohammed appears as a kind nobleman: He deliberately does not touch Aisha, the child, even when she begins to think of herself as a woman and is devoured by her jealousy over the prophet’s exclusive attention to his other wives. It is Mohammed’s reservation that drives the story – it is his restraint that ushers Aisha back into the arms of her childhood friend. Just as in the Islamic tradition, Aisha is no saint; Mohammed, conversely, appears as just that, although even the sources mention his weakness for the female sex.

So why the controversy, you might ask, if the book doesn’t offer anything even to a devout believer that is not already layed out in the Islamic tradition? The Jewel of Medina is no provocation for Islam, but more so for the producers of a western image of Islam at the universities and in the media. It is the scandal of an Islamic science that has itself become fundamentalist and tolerates no gods beside itself. One has to savor this story: Asked for a “blurb”, one of the promotional one-sentence exclamations of enthusiasm on the book cover, Denise A. Spellberg, a historian at the department of Middle Eastern studies at the University of Austin, Texas, reacts with an outcry of horror. The book, she claims, uses islamophobic clichés and could be understood as a provocation by Muslims. But, how did Spellberg arrive at this judgment?

Denise A. Spellberg is the author of a survey from 1994 entitled “Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past. The Legacy of Aisha”. This is an astute deconstruction of the Aisha-legends, using the culture-critical tools developed by the Gender Studies. At a closer look, this is a much greater provocation than Sherry Jones’ novel. However, in judging the novel, Spellberg has turned her own research results into a religion again: According to her, a portrayal of Aisha on the grounds of the legends, which Spellberg had already deconstructed, is unobjective, bad literature, indeed: morally reprehensible. In a letter to the editor of the “Wall Street Journal” on August 9th she demands that “a literature seeking to further civilization should correctly portray history.”

Aside from the fact that the quality of a historical novel cannot be measured by factual accuracy alone, not even Spellberg can know the “right” story in regards to Mohammed and Aisha. If Sherry Jones resorts to a few anachronisms, so be it. What is interesting about the accusations however, is that they amount to a historiographic and aesthetic “truth-fundamentalism” of western provenance, which uses the religious sensitivity of Muslims as ammunition to weigh down its own position. It is a small wonder that some agitators have jumped at this incentive. In the manner of a self-fulfilling prophecy, it was the western assumption of Muslim sensitivities which aroused them in the first place – above all in a case where other than with the Mohammed-caricatures or the Regensburg speech of the pope contained not the merest antiislamic disrespect.

For this reason, The Jewel of Medina is to be recommended, not as a book of scandal or an unusual suspenseful read, but as an entertaining introduction to the world of the Mohammed traditions – to a downright Mohammed epic, as we might be allowed to say. This material, its multifaceted and often contradictory illustration in the Islamic sources is one of the few great narratives of humanity that has yet to be appreciated in the West. Its appropriation, particularly by non-Muslims, is not only desirable from a literary perspective, it is also necessary to prevent the sealing of the material by Islamic fundamentalists. To have taken a first step in the direction of this appropriation, Sherry Jones deserves gratitude from all sides.

Stefan Weidner is editor-in-chief of “Art and Thought, the Journal for Dialogue with the Muslim World, published by the Goerthe Institute.”

The Jewel of Medina

by Nadia’s Sakinah

I just finished this book….and wish, on some level I had read it sooner. There are some progressives who doubt Aisha’s existence at all, and whether one does or does not, it’s a fascinating read. Yes it’s fictional, but it takes a heroine of Islam and makes her personal. It reminds people that both prophet and woman were human, people. With emotions like anger, jealousy, fear, love, kindness. That patience must be learned, that life changes us, and that somewhere in there we have the strength to do the unexpected.

Here’s one by R. DeMarino on www.rateitall.com:

(Five stars)

The Jewel of Medina is a beautiful story portraying the life, struggles and love of Aisha, the second and youngest wife of Muhammed. I found it enjoyable to read (I had a hard time putting it down!) as well as allowing a glimpse into early Islam. Sherry Jones treats the love story between Muhammed and Aisha tenderly: even though Aisha is a child when they marry, you feel that Muhammed loved her dearly and treated her with the utmost of respect. As she grows up her love for Muhammed matures and her desire to be a strong and courageous helpmeet to him emerges. The insight into being a “sister-wife” was facinating and I liked how Sherry Jones depicted the day to day toil – including the jealousy, rivalry, support and love between them. Years ago I read The Story Bible, by Pearl S. Buck, and it made Biblical times so vivid to me! I feel The Jewel of Medina opens up an understanding of early Islam in the same, beautiful way!

And here’s one by Muslim Fundamentalist on www.rateitall.com:

(Five stars)

Most of the muslim reviewers understandably have no comprehension whatsoever of the ways that non-muslim Americans think, or of the value of this book in providing them with an actual ~ as contrasted with the usual utterly falsified ~ history of the establishment of Islam in Arabia during the Medina period. That the fictionalization of the characters into modern American stereotypes is offensive does not change the result that American readers will be able to identify with the factual experiences of the period and assimilate for the first time some semblance of understanding of the birth of the faith that is their true heritage in Abraham. Such hostile and angry reviews are a good illustration of why muslims who are not Americans who have emerged from the American jahiliyyah should not be trying to “explain Islam” to Americans, a task best left to indigenous American muslims. The book is fiction that makes history available to Americans who would otherwise not be remotely interested. However offensive or disappointing the mischaracterization of ‘A’isha, ‘Umar, ‘Ali, and others might be to muslims, any debunking of the falsification of Islam that permeates America’s information media is a good thing, and Jones does this in a way that can reach American readers.

The Jewel of Medina

(Five stars) “Great Historical fiction. I liked the window into the origins of Islam. It humanizes the Prophet Mohammed, focusing on the man and his wives rather than the Koran and Islam. I thought that using A’isha to tell the story gave it an additional angle, that of someone growing up alongside the new beliefs of the faithful.” — Bruce D., Shelfari

From Mandy’s Many Reads

I have to say that this was one of the most well researched books I have ever read. I also think that it took a great deal of courage to portray Mohammed (PBH) as she did. He is portrayed as a real man, full of faults, sexuality and everything else that goes with it. I felt that the last chapters were the most well written of all. There will be a sequel and I am looking forward to it.

Read more Reviews and Testimonials